Hackstar in Exile: My intro to the American Wikileaks rapist

Most of my conversations with Jacob occured on encrypted chat platforms, and I did not save logs. This blog is my attempt to recover the story.

For me, it started the summer of Snowden in 2013. In Guayaquil, Ecuador, I am a journalist working on the web desk of a national newspaper. It's my first paid job in the country. Julian Assange has asylum in Ecuador's embassy in London.

I was on a missionary visa in Ecuador my whole childhood, into my early 20s. I left the church when I started university, in Canada. I had never negotiated my own residency permit in Ecuador; there had always been an elderly American couple, living in a zoo outside the capital city Quito, who we would courier our passports to once a year. They sorted the required stamps and official scribbles on the visa pages for every missionary in the denomination. Coming back to Ecuador as an adult, means figuring out a way to stay here without the church. It doesn't take long, as there is an inherent privilege to being a white person in Ecuador. I write one email to an editor-in-chief of a national newspaper, introducing myself as a Canadian online journalist. Orlando Perez invites me to meet for an interview. At our first meeting, at a coffee shop at a mall, he offers me a job in the web section of his newsroom.

In Ecuador, the Snowden season isn't a summer, it's the tail end of the rainy season and the start of the dry one. While Ed is eating Hong Kong's finest room service with a documentary filmmaker and a legal blogger, and Julian Assange is sampling Knightsbridge's takeout, I am eating sopa de queso at the work cafeteria with my four person team.

Compared to the rest of the newsroom, the web team is young, two of the workers are also part time university students. Before I come along, they were simply copying the articles that the print journalists authored, from the print layout app, and pasting into the web content management system. Orlando wants me to introduce some newer online journalism techniques, like interactive maps and social media curation.

The broadsheet El Telegrafo, established in 1884, was converted into a public institution during the presidency of Rafael Correa (2007 to 2017). President Correa, calling himself a 21st century socialist, expropriated news outlets from a variety of private owners, to create a network of publicly-funded print and broadcast publishers. “When I took office, there were seven national TV channels. Five belonged to bankers,” Correa says to Assange, in their interview together for Julian's show on Russia Today. “These people disguised as journalists are trying to do politics, to destablilize our governments—so no change occurs, to avoid losing their power.”

Power is on my mind as well. After all, I took this job to get a work visa. Given the petty corruption of the local bureacracy, and Correa's open conflict with media companies, I asses my most likely path to getting permission to stay in the country, is working for a state media company. Indeed, Orlando assures me the work permit is on its way, the newsroom lawyers are handling it. By mid-June, my visa hasn't come through yet.

Web section workers rarely get sent out on assignment. The first time Orlando sends me out of the office to attend a conference, I meet a Wikileaks member in Ecuador. To get to the conference, the whole web team squeezes in to one of the minivans that hangs out in the parking lot usually reserved for reporters. The venue is outside the core of the city, across the Daule river at the Parque Histórico, a wildlife reserve and replica of Old Guayaquil built in a wealthy suburb. In high school, I had toured this traditional wooden farmhouse, while a guide introduced us to traditions of the colonial era. Orlando wants the web team to work remotely from desks at the conference, and so the organizers set us up in a room with glass walls like a fishbowl, next to the main stage. We are there as display items, as much as journalists. The publicly-funded media outlets are a key rhetorical part of Correa's proposed new communications law. He says the law isn't meant to restrict the media, but to usher in a new era of socially responsible journalism.

"There is going to be a secret keynote,” Orlando pops into the fishbowl to say. I wander around the backrooms of the replica hacienda home and slip in to the VIP rooms to try to find out who it might be. When I see a an excited posse of groupies and a shock of white hair, my first thought is: maybe Assange finally got safe conduct and snuck out of the UK? But the white head belongs to Kristinn Hraffsson, the Icelandic journalist who joined Wikileaks when they published banking documents from the financial crash in Iceland. Protecting Hraffsson from the scrums, is his partner at the time, a tall American woman, elegant with long black curly hair cascading over her scarf. When I push my way up to the couple and ask for an interview, she answers "no comment," and they quickly disappear deeper into the building. In the outer lounge, I recognize legislator Soledad Buendía, from Correa's political party, and approach her to ask about the new communications law. She talks about being targeted by networked media disinformation, and the need for regulation. I distractedly scan the room behind her for any further sight of the foreigners.

In the afternoon, we find out the secret keynote is indeed Julian Assange, only via video link. Hraffson is there to introduce the remote appearance. President Rafael Correa will also attend the conference, to announce the new Ecuadorian communications law, widely condemned as an attempt to regulate the media. Julian Assange provides rhetorical cover to the Ecuadorian government, as Correa can get credit for protecting the most famous dissident journalist in the world.

”I will be the warming up act,” says Hraffsson in his introduction speech. He cites Cuban poet José Martí “I have been inside the beast and I know its entrails,” and then quips: “I was starting to feel that the entrails were pretty smelly. The mainstream media in the western world has failed the general public especially in the past ten years.”

Meanwhile, on the other end of the video link, an Ecuadorian consul in London, Fidel Narvaez, is helping to arrange the camera and microphone. The connection with the embassy is poor. In the hall in Guayaquil, most of Julian's speech is lost in translation and distorted by the tubes of the internet. The video released sometime later is clearer and easier to understand.

Narvaez was an activist in the protest movements that toppled presidents before the Correa decade. Under Correa, like many left-leaning operators, he became a diplomat. He sympathizes with the Wikileaks' cause, especially the parts about resisting American interference. When Edward Snowden accepts Wikileaks' offer for help to get out of Hong Kong, Narvaez plays a key role.

At Julian's behest, at 4am on June 22 Narvaez signs a diplomatic document called a safe-conduct pass, which is not authorized by his direct superiors in the foreign ministry or by their boss, President Correa. This unofficial safe-conduct pass signed by Fidel is enough for Snowden and Sarah Harrison, Julian Assange's one-time intern and partner, to feel confident enough to try to board an airplane in Hong Kong. In the end, it is an error in the name on the NSA leaker's extradition warrant, that allows Hong Kong's authorities to justify letting Snowden and Harrison cross outside their border. While they are in the air heading to Moscow, Wikileaks releases a statement saying Snowden is seeking asylum in Ecuador. This is confirmed by Ecuador's foreign minister Ricardo Patiño, caught on a trip in Vietnam:

The Government of Ecuador has received an asylum request from Edward J. #Snowden

— Ricardo Patiño (@RicardoPatinoEC) June 23, 2013

In between mugs of lukewarm tea from my office hot water dispenser, I stream the video of Patiño's press conference in Hanoi announcing that Ecuador is considering the request. I live-tweet it in English.

The audio on the BBC feed cut out when the translation of FM @RicardoPatinoEC about US pressure question went through, anyone get it?

— Jacob Appelbaum (@ioerror) June 24, 2013

My first contact with Jake is on his public timeline, telling him to check my Twitter feed to find my translation of Patiño's news conference from Hanoi.

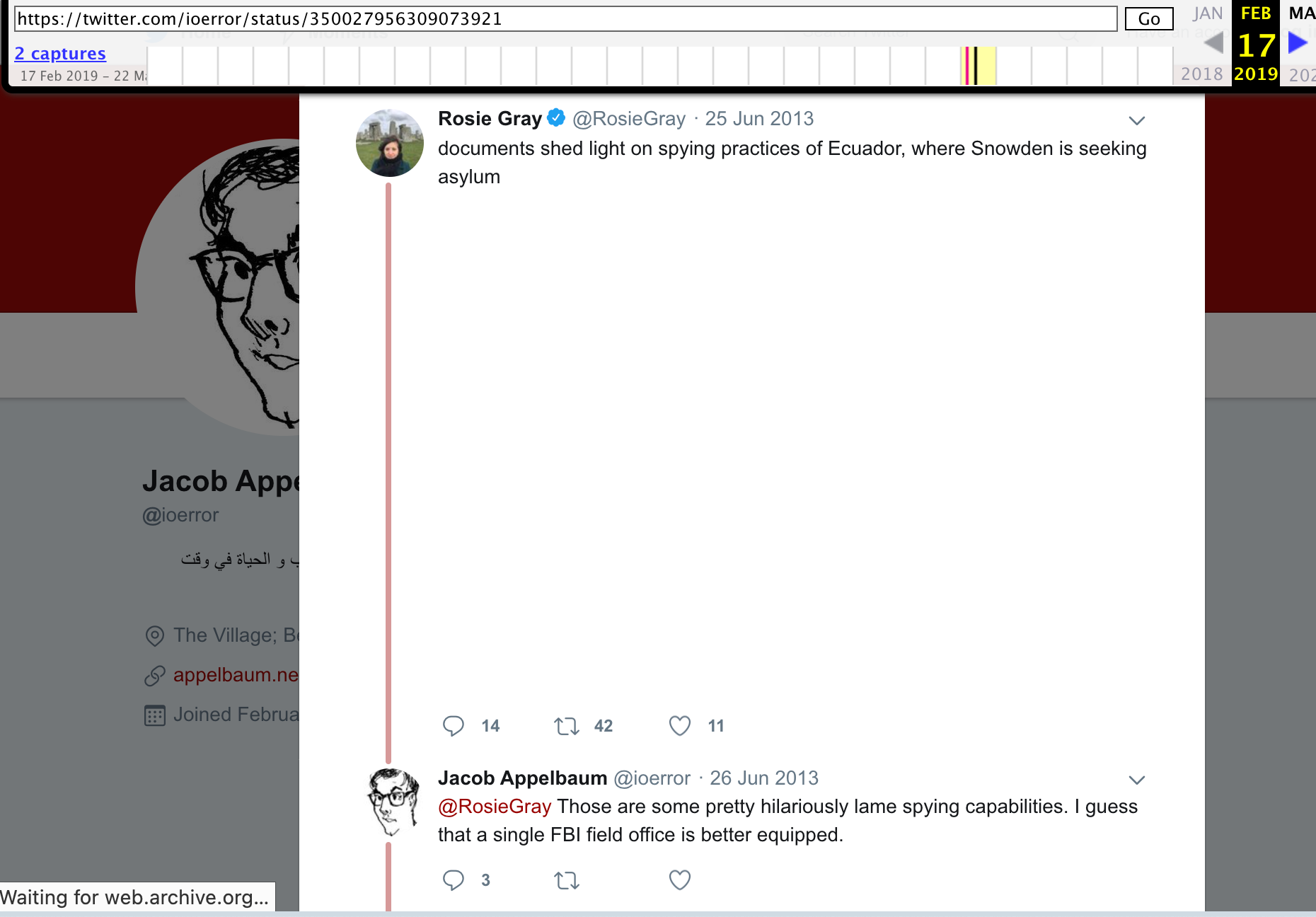

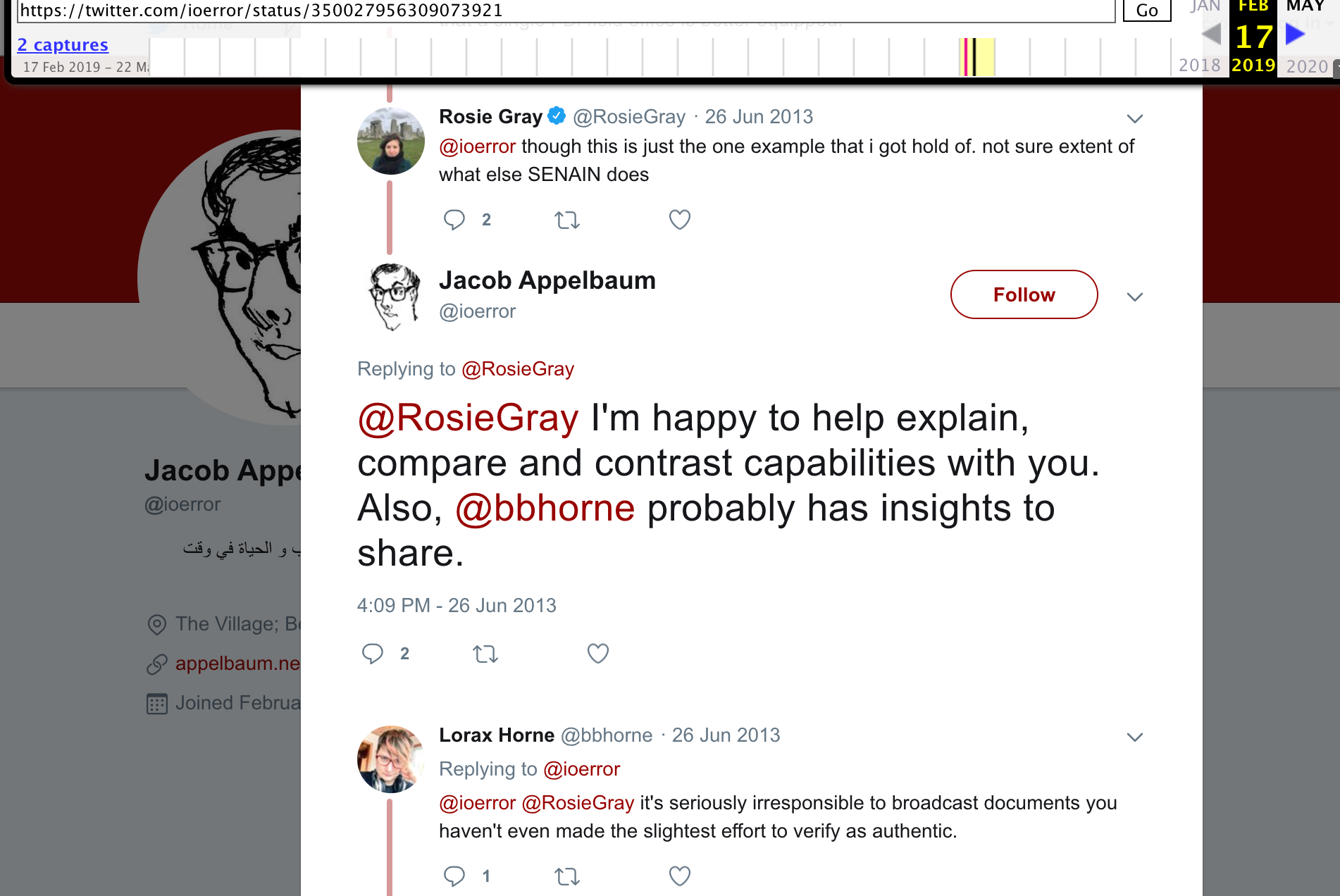

The next day, Jake flatters me in the replies to a story by Buzzfeed's Rosie Gray about domestic spying capabilities in Ecuador.

Gray's article in Buzzfeed is about leaked documents from August 2012. The timing of the documents disclosure to Buzzfeed is suspicious, according to Appelbaum, and seemingly based on a state-sponsored intercept of Ecuadorian government communications. He thinks Gray is a mouthpiece for U.S. foreign policy, delivering a warning from the United States to Ecuador's political class: that if you protect Edward Snowden, expect more secrets to come out.

The next day, Jake flatters me on his public timeline again, complimenting a different story that I wrote, one that was based on a Correa government press release:

Wow @bbhorne just blew my mind about #Ecuador about the War on Some Drugs: https://t.co/9BbpICUgcL

— Jacob Appelbaum (@ioerror) June 26, 2013

Many Ecuadorians think of the ten years under Correa (2007-2017) as a time of rare stability and prosperity. The influence of the government on the content of the newspaper wasn't obvious to me when I started. Working under Orlando the editor-in-chief, a loyal partisan, I was gradually able to see how government policy directly impacted our coverage. Topics that the presidency selected, like a special series about femicide, became newsroom priorities. I later found out that Orlando was suspected of murdering one of his romantic partners with a bomb in the 80s. Female members of the newsroom, already used to being yelled at more, paid less, and given worse assignments, are called into a conference room to recieve a lecture from the biggest bully in the company about why they should care about domestic violence and intimate partner murder.

I came into media work via the journalism school of a small liberal arts college in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Our first homework assignment was to subscribe to the local newspaper, the Daily News. Assignments included interviewing a homeless person, and crafting an inverted-pyramid story based on a random court document. I joined the staff of the student paper, the Gazette, publishing pieces about municipal politics, bands that come to play on campus, and local activism. The Daily News went out of business before the end of my first year. They didn't even get to publish a goodbye issue, they just shut down abruptly with no warning.

I noticed Wikileaks the first time when they put out the video called Collateral Murder in April 2010, my third year. The whole journalism school was buzzing about this new website. Profs in both my journalism ethics and my investigative seminars brought up the video, and the students discussed the question: does Wikileaks count as journalism? I watched both the full length raw feed, and the edited version on YouTube multiple times. In the middle of my courses clinging to the ruins of a crumbling industry, Wikileaks seemed like the future.

The video shows a birds-eye view of U.S. Army snipers inside an Apache helicopter killing civilians and two Reuters journalists on July 12, 2007. The commentary track from the perpetrators is full of bloodlust, expressing disappointment at missing shots, and mistaking the large lens of the camera carried by one of the journalists on the ground for a weapon. The U.S. soldiers mercilessly pummel the blurry figures with machine gun fire until there are no moving humans left on the scene. Reuters fought for years through all the approved channels, and could never get access to the truth about what happened to their employees on that day. In contrast, Wikileaks publishes 39 minutes of raw evidence shot from the Apache’s gun-sight, showing the Iraqi men and children scattering, and framed defenseless and exposed inside a target grid while the story of their deaths is narrated by their shooters. As my university classes trained us to become the Reuters workers on the ground, I coveted the impact of the story told by Wikileaks. I didn’t want to become the person scrambling, running from death from above. I wanted to become the person able to eventually show people what really happened.

A study abroad scholarship took me to a journalism school in Mexico, which I saw as a stepping stone to a job in Spanish-language media back home. My live-in partner, a blues band bass player who was co-parent to our two dogs, said he’d drive our camper van from Halifax to Mexico to join me. I flew with the smaller of the two dogs to Guadalajara, took a taxi two hours towards the coast, and rented a room at the back of a house on a quiet cobbled street in the city of Colima. The room had no windows, and the only method for cooking was a microwave. I fell into a depression. Within a month, my long distance relationship with the bass player fell apart. I bought a liter of tequila, walked the dog, and cried all day, missing classes.

I had met Camila, another exchange student from Canada, at orientation. Her dad worked for an oil company. When I stopped coming to class, the university asked her to check on me, and she showed up in her father’s SUV to bring me to live with her in their gated community. Still unable to function without gulping down tears in great heaving fits, I dropped out of school. I called my dean in Canada sobbing and they accept that I will forfeit the scholarship. Camila was still going to her classes and training at her tennis club, while I ate their food and swam alone in the neighbourhood pool. I wailed underwater, where nobody could hear it. Eventually I left with my backpack on a bus to Mexico City in a haze, with the dog smuggled into a carrier under my arm.

I thought travel might help me feel better, but Mexico didn't remind me of Ecuador at all. Leaving Camila and Colima behind only made the loneliness worse. For the first time in my life, I was suicidal. Images of throwing myself under the trains in the largest city on the continent flashed through my mind when I descended into the subway tunnels. I stopped myself by imagining my aggressive Jack Russell terrier’s life as a Mexican street mutt, replaying the movie Amores Perros that I watched in one of my film studies courses. I rented a cheap windowless hotel room in the old city, a couple blocks from the huge open square, the Zócalo. The hotel had no wifi, so I bought stacks of pirated DVDs in the black market in Tepito, then holed up to bingewatch ripped TV series and consume all the podcasts on my laptop.

I found out on Facebook that my friend Laura from university was traveling nearby. Volunteering with the Zapatistas in Chiapas, she had a heartbreak of her own. I met her at her backpacker’s hostel near the Zócalo. Laura suggested a day trip to the Teotihuacan pyramids one day, and to the botanical gardens the next. Finally, she breathed enough life into me that I booked a flight back to Toronto with the dog.

I was afraid to face Halifax, my ballooning student loans and the aborted scholarship for the study abroad term. I moved in with my aunt and uncle in Waterloo, Ontario, in the same room I lived in for a couple of terms when I was finishing high school. I was still afraid to be anywhere alone after the intrusive fantasies of self-harm in Mexico.

On Twitter one day, I read about a new journalism start-up in Toronto. While I was not ready to go back to school, I knew I might enjoy working again. Figuring the start-up building its brand might accept an unpaid intern, I reached out to ask for a place in their office. To my delight, they accepted. Completing a one month unpaid internship also happened to be one of the requirements for graduating from journalism school. While I was still undecided about going back to the degree, I thought I might as well check off the box of the unpaid internship. I moved in with my grandfather in the condo he bought after my grandmother died, on the outskirts of Toronto.

The start-up, OpenFile, wanted to democratize the news gathering operation by engaging a readership in the early stages of story development, letting anyone “open a file”, and paying young journalists to gather the crowdsourced raw material, report on the threads that emerged, and follow the story. OpenFile worked a bit like the Wikileaks model, by inspiring new sources to recognize their agency in the news, but with items of OSINT instead of classified documents. Three journalist co-founders backed by investors hired a design firm and an accountant to work in their open plan office. They assigned me a desk in the corner and let me write in exchange for school credit and train tickets. I impressed the small staff with my efforts, and they offered me a freelance summer position, which I accepted.

My first job in commercial media had me covering the tips coming in from our audience as Toronto prepared to host a G20 summit. My friends from Halifax drove 20 hours to join the street protests against the gathering of world leaders. My ex travelled to the protest as well, the first time I saw him since we broke up over Google chat. I avoided any fantasies of jumping in front of the Toronto subway by keeping myself busy and diving into work. Laura was back from Mexico. She and I woke up at 6 am on the first day of the protests to wheatpaste pro-abortion posters around Bloor Street. I attended teach-ins at Ryerson University about how to detox from tear gas and pepper spray, and how to link arms wrapped in metal chains inside PVC pipes to create human barriers.

Because my gig with OpenFile was part time, I spent a lot of time with my friends from Halifax who were there for the protests. The activist trainers recommended getting a protest buddy, and fitting our duo into a larger unit called an affinity group, including at least one person kitted-out as a medic. My ex was in our affinity group, so Laura and I became medics. We filled our backpacks with gauze and squeeze bottles with watered-down Maalox. The role allowed us to break off from the group and attend to head injuries and exhaustion cases happening on the edges of the march. I wrote about some of the police brutality incidents for OpenFile. In between the daily events, I interviewed environmentalists, queers, immigrants, and anti-poverty organizers, who imagined better solutions to the world’s problems than the show of force that Canada’s prime minister Stephen Harper had assembled in the Ontario capital to impress Obama, David Cameron, Angela Merkel, Nicolas Sarcozy, and Silvio Berlusconi.

From my office in the gentrified neighbourhood of Liberty Village, I walked to the activist’s field center in the working class area of Parkdale. We hung out at the free food kitchen and saw police arresting people, including the cook, for no reason. The security angle of the summit peaked my interest. I attended a meet-up called Hacks and Hackers, which brought technologists together with journalists to discuss building tools for better civic engagement. The day before the biggest protest march, police arrested security consultant Byron Sonne on terrorism charges. Sonne had been posting photographs of the fence around the summit zone, and suggestions on how to dismantle it. Sonne was a member of the Hacks and Hackers Toronto gathering, one who I never met in person. Sonne became a cause célèbre for technical people who were concerned about police powers. He was eventually cleared of all charges, after losing his home and marriage in the course of the case.

Between Her majesty the Queen and Byron Sonne, I'm glad Byron Sonne came out on top. He deserves serious compensation for his losses.

— Jacob Appelbaum (@ioerror) May 15, 2012

Over the long weekend, ten thousand police corralled protesters, pushing them with bikes and chasing them with horses, kettling hundreds, and locking up dozens in an improvised jail without food or bathrooms. I made an interactive map of the new network of CCTV cameras that Toronto police bought and installed ahead of the summit. My employer didn’t have the brand recognition to get a press pass to the summit, so instead of talking to politicians and diplomats, I covered what was going on outside.

On Twitter, I noticed the curious language used by a cop who arrested someone downtown. The police officer said the person couldn't decline to be searched, as they didn’t have those Charter rights in the area near the fence. By texting my editor quotes from a flip phone, I broke the story of a World War I-era provincial law that the government secretly activated to suspends civil liberties in the area around the summit. Contrary to the conventional know-your-rights instructions we were getting in our trainings, under the new law police could force people to show their identification, and could search bags without a warrant, in a defined area of downtown Toronto close to the summit fence. Toronto shipped in police from all over the province and elsewhere in Canada, to enforce this new civil liberty-free zone.

The experience covering the summit convinced me to go back to try to finish my degree. The dog and I made our way back to Halifax. The cohort I started Journalism 101 with was graduating. Because of the aborted study abroad term, I didn’t have the credits. By now, everybody in the world had heard of Wikileaks. Julian Assange was wanted for questioning in Sweden after two women accused him of sexual assault. Assange was working with The Guardian to report on cables from the US State Department. These private communiques between Washington and their foreign missions embarrassed US diplomats all over the world, including back home in Ecuador, where the US ambassador was expelled and the national chief of police was fired over the content of the cables. My high school in Guayaquil was called the American School. In addition to the flag of Ecuador, we flew a stars-and-stripes on our courtyward, and sang the American anthem during assembly on Mondays. Like many official American Schools around the world, my high school began with funding from the US embassy. I used the Wikileaks search engine to find all the mentions of my high school in the diplomatic mail. The source of the US State department cables, and of Collateral Murder, had been arrested: the soldier Manning faced a court martial, and a charge of “aiding the enemy,” akin to treason.

OpenFile was growing and expanding into Halifax. They wanted to open a newsroom there, and hired me as the city curator, in charge of writing most of the content. I dropped out of my last university class to work as a full-time contractor. Thanks to the start-up's angel investors, which turned out to be TD Bank, the pay at OpenFile was better than freelancing at other local websites. Only a year later, we found out that the founders failed to attract any new investors. With little warning, the whole network of sites shuts down, a year after our launch in Halifax. I became a whistleblower, and one of the only named sources to speak to the Canadian media about the implosion of the company. As a result, my job prospects in Canada are slim.

I collected my last pay cheque and use savings to move back to Ecuador, to look for work. At this point, Julian Assange has claimed asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London. I miss my friends in Guayaquil, and also I am curious how Ecuadorian society is reacting to their new role as international bastion of free speech. The president elected when I left for university, Rafael Correa, is still in power and consolidating his influence. Local journalists are fighting against the new Correa law supposed to regulate the media. Chelsea Manning, Julian's source, has not been sentenced. She is not yet out as trans, but in a leaked chat published by Wired magazine, she tells the snitch Adrian Lamo that she prefers a female name. I probably noticed this frustrated coming out story, because I, too was trans, and in the closet.

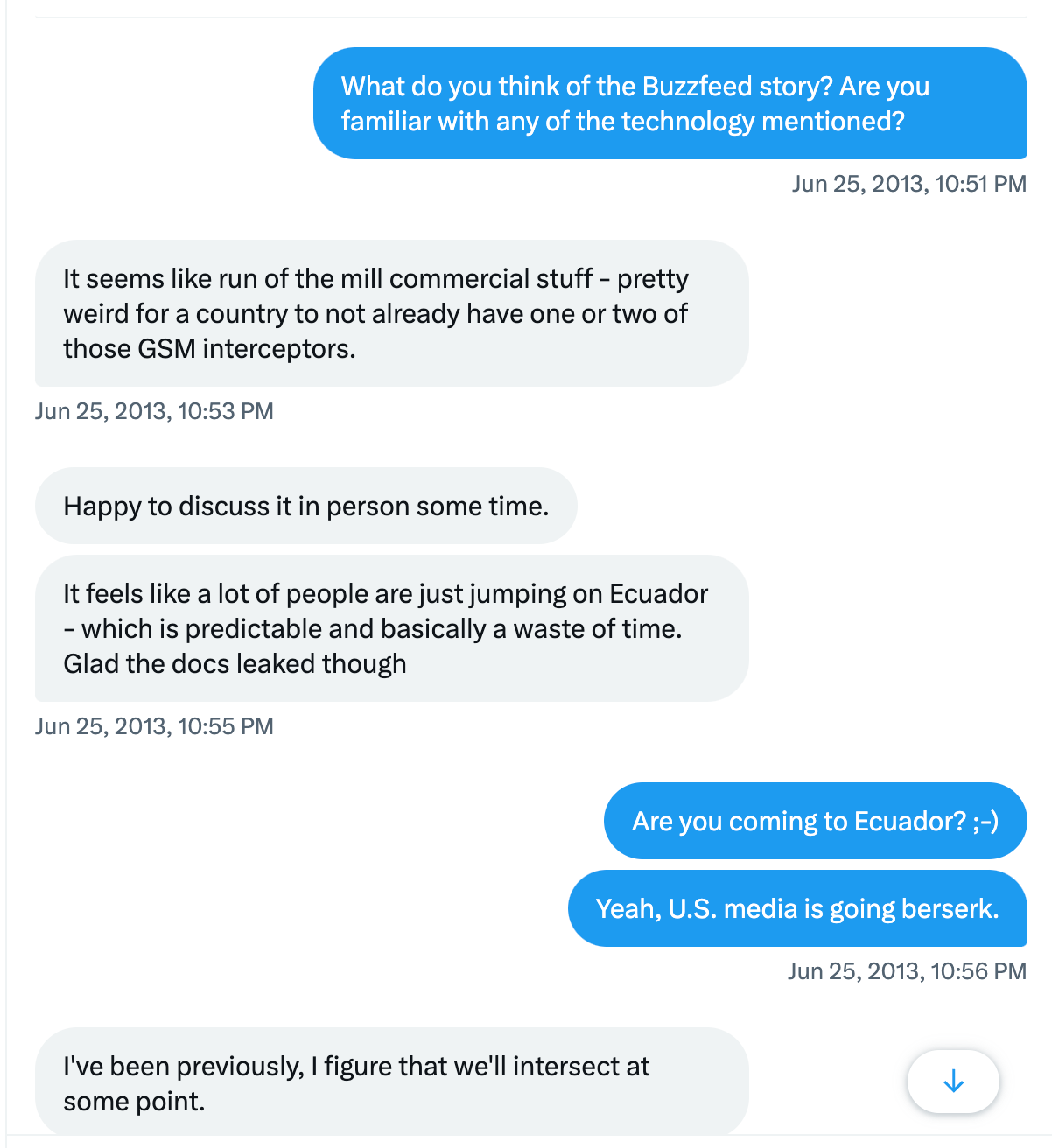

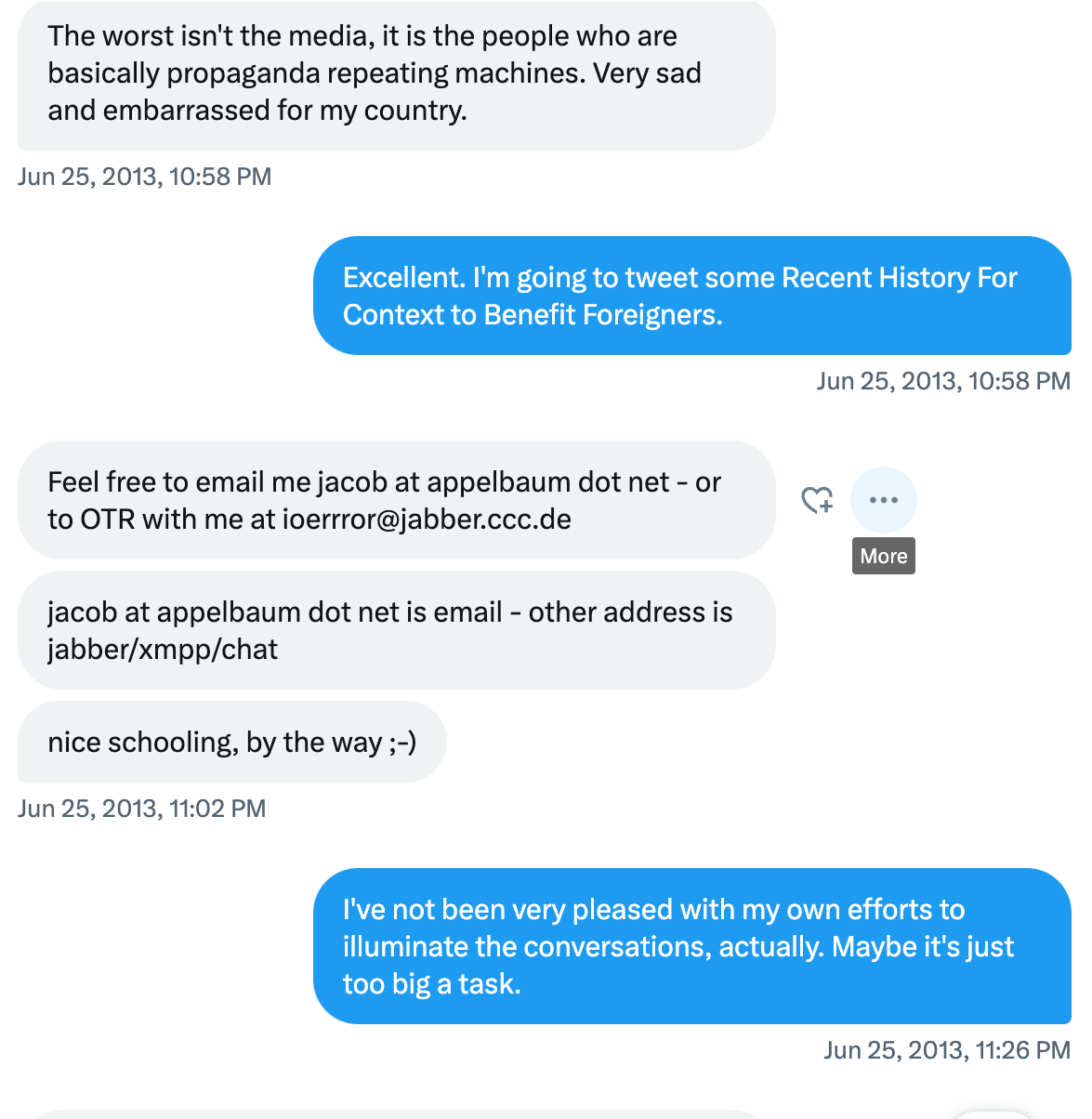

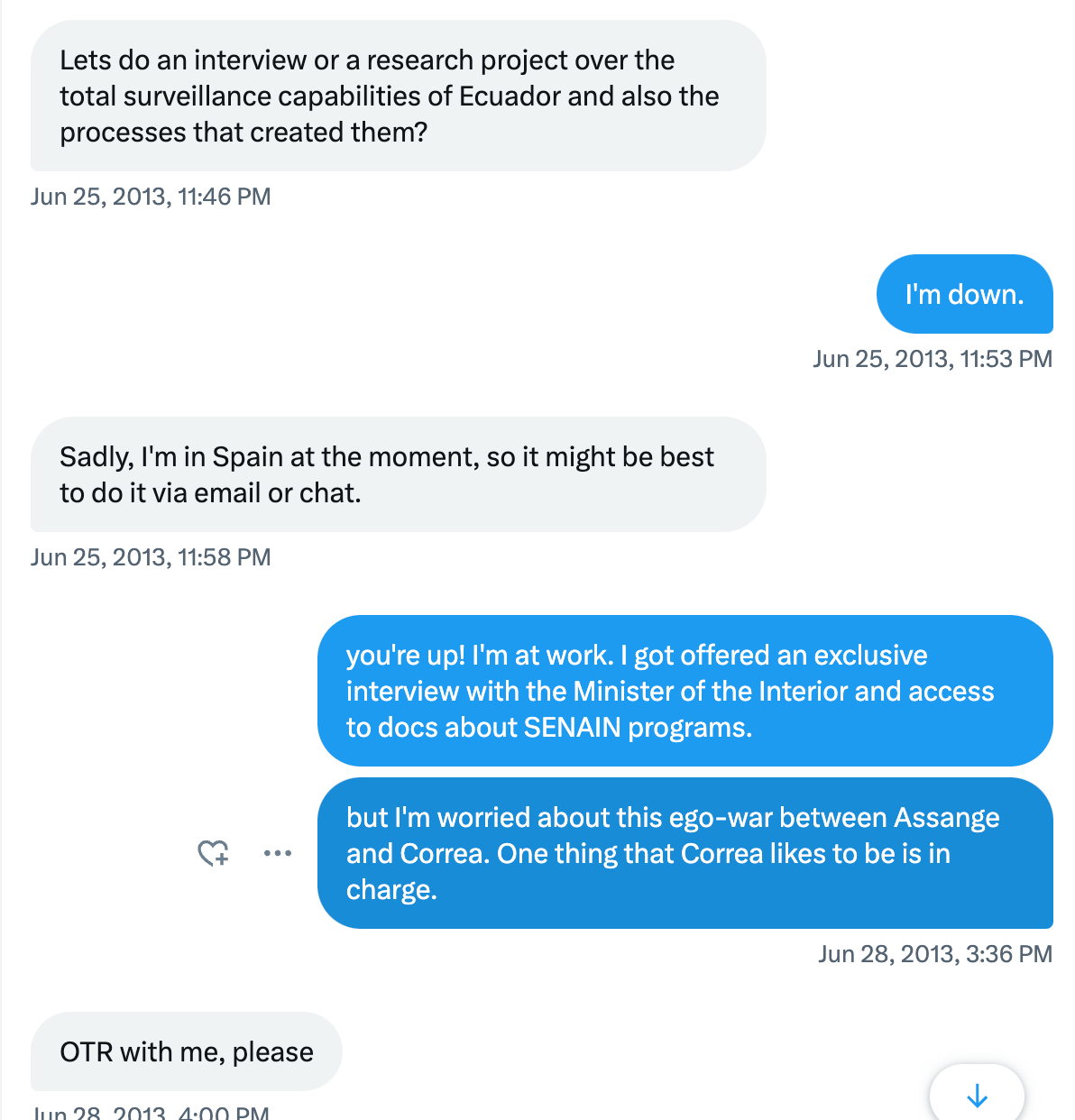

After Jacob Appelbaum's flattery of my work on my public Twitter timeline, I look up his name and read the Rolling Stone article about him. Then, I slide into Jake's DMs to learn more about this Wikileaks thing, purporting to interview him about Rosie Gray's story about Ecuador's domestic spying.

What is OTR? At that point, I had to look it up. Once I install the required chat program and turn on all the widgets to encrypt our conversation, Jacob helpfully points me to a link explaining how he contributes to writing the protocol.

What follows, is my induction into what I can only describe now as the Wikileaks cult. Most of my conversations with Jacob in the years after 2013, occured on encrypted chat platforms, and I did not save logs. This blog is my attempt to recover the story from the depths of my memory.

Thanks for reading.